by Jan Robert Go

26 March 2021 – 武汉,每天不一样。 Wuhan, different every day.

For many, Beijing and Shanghai are the go-to places in China, while Chinese Filipinos would also know Fujian’s Xiamen. But Wuhan is most likely a never-heard-of place. Located in central China, the city is a bustling metropolis and is traversed by the Yangtze River, Asia’s longest river. Wuhan has been a home to me for almost three years now. I arrived here in 2018 to pursue further studies.

By December 2019, Wuhan had become the centre of attention when cases of pneumonia with an unknown origin were recorded in the city. Three weeks into 2020, the city was placed under lockdown to control the spread of the disease, which was later named coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

In this piece, I talk about the days under lockdown and share my brief impressions on the Wuhan government’s actions and community involvement. This is less of an academic analysis and more of sharing my experiences.

* * *

~taken on 26 January 2020, three days after the city was placed on lockdown~

When Wuhan was placed on lockdown, people here had a mix of feelings.

There was a sense of uncertainty. Nobody knows how long the lockdown will last. The official announcement only gave the day and time when it starts, but not when it will be lifted. I remember people lining up in supermarkets and buying as much food they can. Food shops and establishments were closed.

There was also a sense that things were more severe than expected. The lockdown was seen as a radical policy choice. It entailed suspending public transportation and closing of all portals in and out of the city. It meant shutting down the city two days before the Chinese Lunar New Year celebrations.

In my university, a building lockdown was implemented. No student was allowed to leave their building except for emergencies. We were supplied with three meals a day, face masks, hand washing soap, and one-time electricity and water subsidy. Clueless with what was to come, I, along with my fellow international students, tried to live with whatever we had at that time.

Each student was given a thermometer and required to record their body temperature three times a day. This was crucial for the first 14 days. As it was wintertime in Wuhan, the

weather was cold, and many were developing what could be considered minor symptoms of the disease. Day in, day out, there was a building sense of paranoia for some.

The Department of Foreign Affairs arranged repatriation flights for Filipinos in Wuhan. Many friends, relatives, and colleagues asked if I would avail of the flight. The Philippine Consulate in Shanghai was in constant contact for updates on my situation and decision. At that time, the Philippines only had less than 10 cases. I decided to stay.

The spring semester began during the middle of the lockdown. The online classes gave us something to be busy with and help us forget about the situation, albeit briefly. New difficulties emerged as online classes had been challenging. But at that time, we had no choice but to continue.

Late March 2020, we were given a glimmer of hope. The government announced the lifting of the lockdown. This was gradually implemented in our university to ensure that the safe space created during the building and city lockdowns would not be wasted.

We were allowed to leave our dormitories by 6 April. I was inside the building for 65 days.

~taken on 8 April 2020, when Wuhan was reopened~

* * *

Several local government strategies were crucial in the virus control and prevention efforts. At each level of governance, there is a control and prevention committee that oversees the management of the situation. Even in my university, there is an equivalent office in charge of the campus-level protocols and procures materials and resources.

From 14 May to 1 June 2020, Wuhan tested 9,899,828 people. I was one of those who was tested. The government shouldered the expenses for the testing. While the entire project cost 900 million RMB, the sense of security and confidence this has given to the people of Wuhan is priceless.

There is also a mobile application for the entire Hubei Province that generates a health code for each individual, indicating if the person has been tested and the result. A green code means the person tested negative for COVID-19 and is healthy. A grey code means ‘in process’, while a red code means there are symptoms, and the person must limit large-crowd interaction. The app also serves as a contact-tracking system.

In an unprecedented situation like a pandemic, the first response would mostly be reactive. But later on, more proactive strategies were planned and implemented that helped the city to get back and keep going.

* * *

武汉,加油!” Wuhan, you can do it!”

Perhaps one of the key actors in the success of Wuhan’s prevention and control efforts, apart from the government, are community volunteer organizations.

There are open spaces for public participation in the management of local community affairs. Community organizations assist the government, at various levels, in implementing policies. Sometimes, the organizations put up their activities to complement those of the government.

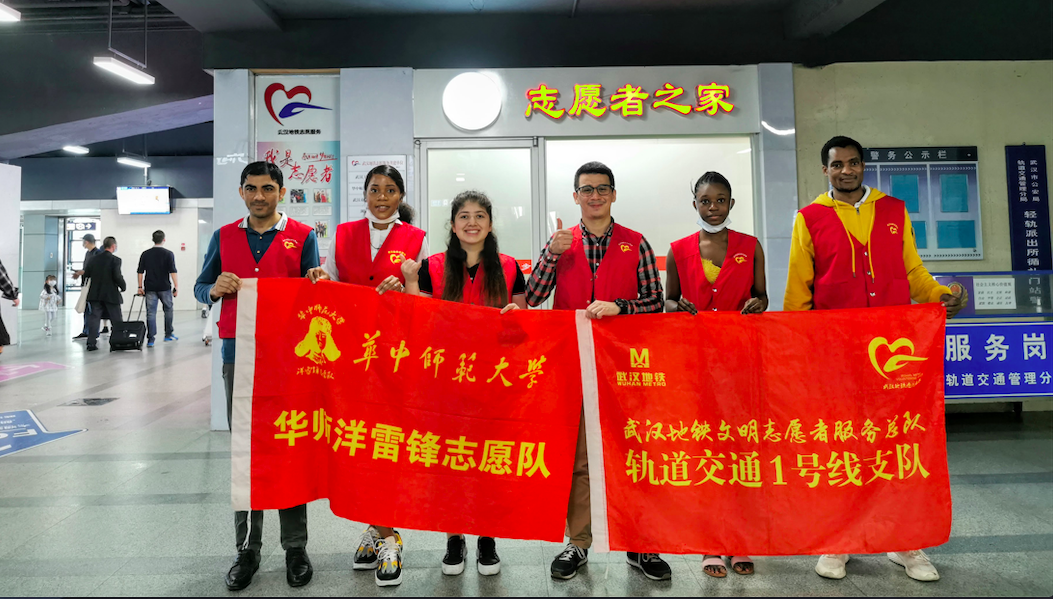

Jan Robert fourth from left (center) ~Volunteer work in one of the subway stations in Wuhan~

Inside my university, the volunteer organisations have been very active especially since the lockdown was during the winter break when staffing was limited. There were volunteers in charge of cooking and delivering meals to different buildings, and there were volunteers to assist in the medical needs of the students and staff.

The university also tapped student volunteers. I was one of the volunteers who assisted in information dissemination and meal distribution. At one point, I was also in charge of taking orders and delivering fruits to my fellow students in the building.

After the lockdown, the organizations and volunteers helped in ‘restoring’ everyday life. Since most establishments were still closed, community markets were set up via WeChat to provide for the food and other basic needs of families. Volunteers also operated barber shops for those who needed a new look post-lockdown.

How the community worked together is an inspiration. Despite the challenges the people encountered, they persevered and pursued efforts to make their community ‘build back better’.

* * *

~taken February 13 (2021), a preview of Wuhan today, this is in Han Street in Wuchang District~